Coin

A coin is usually a piece of hard material, generally metal, usually in the shape of a disc, and most often issued by a government. Coins are used as a form of money in transactions of various kinds, from the everyday circulation of the United States quarter, to the storage of vast amounts of bullion. In the present day, coins and banknotes make up the cash forms of all modern money systems. Coins made for circulation (general monetized use) are usually used for lower-valued units, and banknotes for the higher values; also, in most money systems, the highest value coin is worth less than the lowest-value note. The face value of circulation coins is usually higher than the gross value of the metal used in making them.

Exceptions to these rules occur for non-monetized "bullion coins" made of silver or gold (and, rarely, other metals, such as platinum or palladium), intended for collectors or investors in precious metals. For examples of modern gold collector/investor coins, the United States mints the American Gold Eagle, Canada mints the Canadian Gold Maple Leaf, and South Africa mints the Krugerrand. The U.S. Eagle coin has a "face value" of ten U.S. dollars (and theoretically could be used to pay for goods or services worth ten dollars), and the Double Eagle has a "face value" of twenty U.S. dollars, but these denominations are historical references to pre-depression times when this was the case; of course, these face values are no longer relevant, since the market value of the coin, and the gold in it, is many times the face amount. The Canadian Gold Maple Leaf also has nominal face value, but the Krugerrand does not.

Historically, a great number of coinage metals (including alloys) and other materials have been used practically, impractically (i.e., rarely), artistically, and experimentally in the production of coins for circulation, collection, and metal investment, where bullion coins often serve as more convenient stores of assured metal quantity and purity than other bullion.

Coin collecting is the collecting or trading of coins or other forms of legally minted currency. Frequently collected coins often include those that were in circulation for only a brief time, those that are considered rare because they were only minted for a short time, coins that were minted with errors or foreign coins. Though both are closely related, coin collecting as a hobby can be differentiated from numismatics in that the latter is the scientific study of currency.

The value of a coin

In terms of its value as a collector's item, a coin is generally made more or less valuable by its condition, specific historial significance, rarity, quality/beauty of the design and general popularity with collectors. If a coin is deeply lacking in any of these, it is unlikely to be worth much. Bullion coins are also valued based on these factors, but are largely valued based on the value of the gold or silver in them.

Most coins nowadays are made of a base metal, and their value comes from their status as fiat money. This means that the value of the coin is decreed by government fiat (law), and thus is determined by the free market only as national currencies are subjected to arbitrage in international trade. This causes such coins to be monetary tokens in the same sense that paper currency is, when the paper currency is not backed directly by metal, but rather by a government guarantee of international exchange of goods or services. Some have suggested that such coins not be considered to be "true coins" (see below). However, because fiat money is backed by government guarantee of a certain amount of goods and services, where the value of this is in turn determined by free market currency arbitrage, similar to the case for the international arbitrage which determines the value of metals which back commodity money, in practice there is very little practical economic difference between the two types of money (types of currencies).

Sometimes, coins are minted that have fiat values lower than the value of their component metals, but this is never done intentionally and initially, and happens in due course later in the history of coin production due to inflation, as market values for the metal overtake the fiat declared face value of the coin. Examples of this phenomenon include the pre-1964 US dime, quarter, half dollar, and dollar, US nickel, and pre-1982 US penny. As a result of the increase in the value of copper, the United States greatly reduced the amount of copper in each penny. Since mid-1982, United States pennies are made of 97.5% zinc coated with 2.5% copper. Extreme difference between fiat values and metal values of coins causes coins to be removed from the market by illicit smelters interested in the value of their metal content. In fact, the United States Mint, in anticipation of this practice, implemented new interim rules on December 14, 2006, subject to public comment for 30 days, which criminalize the melting and export of pennies and nickels.[1] Violators can be punished with a fine of up to $10,000 and/or imprisoned for a maximum of five years.

To distinguish between these two types of coins, as well as from other forms of tokens which have been used as money, some monetary scholars have attempted to define by three criteria that an object must meet to be a "true coin." [citation needed] These criteria are:

- It must be made of a valuable material, and trade for close to the market value of that material.

- It must be of a standardized weight and purity.

- It must be marked to identify the authority that guarantees the content.

It is believed by some scholars that the first coins (following the criteria above) were manufactured in Lydia, but apart from one example with the legend "I am the badge of Phales," these pieces have no writing on them, merely symbolic animals. Therefore it is pure guesswork to date the coins, and numismatists' only clue is that some were found buried under a temple from the early 6th Century B.C.E. Many great classical numismatists have debated whether these coins may have been struck (manufactured) under the authority of private individuals, although, as the coins get more common, it is certainly thought that some were made under King Croseus.

The first European coin to use Arabic numerals to date the year minted was the Swiss 1424 St. Gallen silver Plappart.

First coins

The question of the world's first coin has been, and still is debated. While it is believed by many that the Lydian Lion trite is the world's oldest coin, some argue that India's karshapanam is the world's first coin.[1][2] On the other hand, some argue that Indian coins were developed from Western prototypes, which the Indians came in contact with through Babylonian traders.[3]

Coin debasement

Throughout history, governments have been known to create more coinage than their supply of precious metals would allow. By replacing some fraction of a coin's precious metal content with a base metal (often copper or nickel), the intrinsic value of each individual coin was reduced (thereby "debasing" their money), allowing the coining authority to produce more coins than would otherwise be possible. Debasement sometimes occurs in order to make the coin harder and therefore less likely to be worn down as quickly. Debasement of money almost always leads to price inflation unless price controls are also instituted by the governing authority.

The United States is unusual in that it has only slightly modified its coinage system (except for the images and symbols on the coins, which have changed a number of times) to accommodate two centuries of inflation. The one-cent coin has changed little since 1864 (though its composition was changed in 1982 to remove virtually all copper from the coin) and still remains in circulation, despite a greatly reduced purchasing power. On the other end of the spectrum, the largest coin in common circulation is 25 cents, a low value for the largest denomination coin compared to other countries. Recent increases in the prices of copper, nickel, and zinc, mean that both the US one- and five-cent coins are now worth more for their raw metal content than their face (fiat) value. In particular, copper one-cent pieces (those dated prior to 1982 and some 1982-dated coins) now contain about two cents' worth of copper. Some denominations of coins that were formerly minted in the United States are no longer made. These include coins with a face value of two cents, three cents, twenty cents, half cent, the somewhat controversial quarter cent, two dollars, two dollars fifty cents, three dollars, four dollars, five dollars, and half dime (five cents but made of silver and much smaller than a dime). Half-dollar and one dollar coins are still produced but rarely used. The U.S. also has bullion and commemorative coins with the following denominations:$5, $10, $20, $50, and $100.

Features of modern coinage

The milled, or reeded, edges still found on many coins (always those that were once made of gold or silver, even if not so now) were originally designed to show that none of the valuable metal had been shaved off the coin. Prior to the use of milled edges, circulating coins commonly suffered from "shaving," by which unscrupulous persons would shave a small amount of precious metal from the edge. Unmilled British sterling silver coins were known to be shaved to almost half of their minted weight. This form of debasement in Tudor England led to the formulation of Gresham's Law. The monarch would have to periodically recall circulating coins, paying only bullion value of the silver, and re-mint them.

Traditionally, the side of a coin carrying a bust of a monarch or other authority, or a national emblem, is called the obverse, or colloquially, heads. The other side is called the reverse, or colloquially, tails. However, the rule is violated in some cases. [2] Another rule is that the side carrying the year of minting is the obverse, although some Chinese coins, most Canadian coins, the British 20p coin, and all Japanese coins, are an exception.

The orientation of the obverse with respect to the reverse differs between countries. Some coins have coin orientation, where the coin must be flipped vertically to see the other side; other coins, such as British coins, have medallic orientation, where the coin must be flipped horizontally to see the other side.

The exergue is the space on a coin beneath the main design, often used to show the coin's date, although it is sometimes left blank or containing a mintmark, privy mark, or some other decorative or informative design feature. Many coins do not have an exergue at all, and they are most common on coins with little or no legends such as the Victorian bun penny.

Coins that are not round (British 50 pence for example) usually have an odd number of sides, with the edges rounded off. This is so that the coin has a constant diameter, and will therefore be recognised by vending machines whichever way it is inserted. If a coin had an even number of sides this would not be possible. Some such older designs remain, however, such as the 12-sided Australian 50 cent coin.

Coins are popularly used as a sort of two-sided die; in order to choose between two options with a random possibility, one choice will be labeled "heads" and the other "tails," and a coin will be flipped or "tossed" to see whether the heads or tails side comes up on top. See Bernoulli trial; a fair coin is defined to have the probability of heads (in the parlance of Bernoulli trials, a "success") of exactly 0.5. A widely publicized example of an asymmetrical coin is the Belgian one euro coin [3]. See also coin flipping.

Coins are sometimes falsified to make one side weigh more. Such a coin is said to be "weighted."

Some coins, called bracteates, are so thin they can only be struck on one side.

Bi-metallic coins are sometimes used for higher values and for commemorative purposes. In the 1990s, France used a tri-metallic coin. Common circulating examples include the €1, €2, British £2 and Canadian $2.

Guitar-shaped coins were once issued in Somalia, Poland once issued a fan-shaped 10 złoty coin, but perhaps the oddest coin ever was the 2002 $10 coin from Nauru, a Europe-shaped coin.[4]

The Royal Canadian Mint is now able to produce holographic-effect gold and silver coinage.

For a list of many pure metallic elements and their alloys which have used in actual circulation coins and for trial experiments, see coinage metals. [5]

History of coins

The history of coins extends from ancient times to the present. Coins are still widely used for monetary and other purposes. Any history of coins is going to be very incomplete, money being a central theme in human history since its invention. One could approach the history of minting technologies, the history shown by the images on coins, the history of economics, the history of coin collecting or collectors, or many other topics.

A recently published history of the greatest treasures and hoards ever found is fascinating reading. Many histories have been published of the politics around the creation of a single coin, notably the crime of 1873 and its connection to silver coinage of the United States. The history of mining, and various gold and silver rushes and their associated pioneer coining efforts are also extremely interesting reading. Even something as lowly as the history of counterfeiting leads one in a thousand interesting directions. Numismatics is, by its very nature, the study of history. Coins have often been referred to as "History in Your Hands."

In a tomb of Shang Dynasty dating back to 11th century B.C.E. shows the first cast copper money.

All western histories of coins begin with their invention between 643 and 630 B.C.E. in Lydia. Since that time, coins have been the most universal embodiment of money. These first coins were made of electrum, a naturally occurring pale yellow mixture of gold and silver.

Also the Persian coins were very famous in the Persian and Sassanids era. There are lots of coins that have been found in Susa and in Ctesiphon

The most famous and widely collected coins of antiquity are Roman coins and Greek coins.

The Byzantine Empire minted many coins, including very thin gold coins bearing the image of the Christian cross and various Byzantine emperors.

Minting Technologies

Ancient coins were produced through a process of hitting a hammer positioned over an anvil. The Chinese produced primarily cast coinage. Relatively few non Chinese cast coins were produced by governments, however it was a common practice amongst counterfeiters. Since the early 1700s, presses have been used, beginning with screw presses and progressing in the 1800s towards steam driven presses. Recently modern minting techniques involving electric and hydraulic presses have been more commonly employed.

Token coins

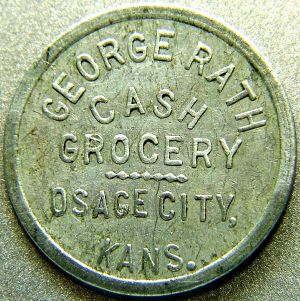

In the study of numismatics, token coins or tokens are coin-like objects used instead of coins. The field of tokens is part of exonumia. Tokens are used in place of coins and either have a denomination shown or implied by size, color or shape. They are often made of cheaper materials than the precious metals: copper, pewter, aluminium, brass and tin were commonly used, while bakelite, leather and other less durable materials are also known.

The key point of difference between a token and a coin is that a coin is issued by a local or national authority and is freely exchangeable for goods or other coins, whereas a token has a much more limited use and is often (but not always) issued by a private company, group, association or individual. In the case of "currency tokens" issued by a company but also recognised by the State we have a convergence between token coins and currency. The best known example, the trade tokens of Strachan and Company, were issued in South Africa in 1874 and are today recognised as that country's first widely circulating indigenous currency.

Currency tokens

In their purest form currency tokens issued by a company crossed the boundary of merely being "trade" tokens when they were sanctioned by the local government authority. This was sometimes a measure resulting from a severe shortage of money or the authority's inability to issue its own coinage. In effect the organisation behind the tokens became the regional bank.

One well-known example of currency tokens are the Strachan and Co tokens which were first issued in 1874 in a remote part of South Africa known as East Griqualand. A partner in Strachan and Co, Charles Brisley, was also the government secretary and obtained official recognition of the tokens as currency for that region. The Standard Bank of South Africa notes in its official archives that its branch in Kokstad, East Griqualand's capital, readily exchanged these tokens as currency in the 1800s because of the shortage of coinage of the crown in the region. These tokens were South Africa's first widely circulating indigenous currency.

Similarly, in times of high inflation, tokens have sometimes taken on a currency role. An example of this is Italian or Israeli telephone tokens, which were always good for the same service (i.e., one call) even as prices increased. New York City subway tokens were also accepted sometimes in trade, or even in parking meters, since they had a set value.

Trade Tokens or Barter tokens

From the 17th to the early 19th Century in the British Isles and North America these were commonly issued by traders in times of acute shortage of coins of the state to enable trading activities to proceed. The token was in effect a pledge redeemable in goods but not necessarily for coins. These tokens never received official sanction from government but were accepted and circulated quite widely.

In England the production of copper farthings was permitted by royal licence in the first few decades of the 17th Century, but production ceased during the English Civil War and a great shortage of small change resulted. This shortage was felt more keenly because of the rapid growth of trade in the towns and cities, and this in turn prompted both local authorities and private traders to issue tokens.

These tokens were most commonly made of copper or brass, but pewter, lead and occasionally leather tokens are also found. Most were not given a specific denomination and were intended to pass as farthings, but there are also a large number of halfpenny and sometimes penny tokens. Halfpenny and penny tokens usually, but not always, bear the denomination on their face.

Most such tokens indicate the name of their issuer, which might either be his or her full name or initials. Where initials were provided it was common practice to provide three, one for the surname and the other two for the first names of husband and wife. Tokens would also normally indicate the trading establishment concerned, either by name or by picture. Most were round, but they are also found in square, heart or octagonal shapes.

Thousands of towns and traders issued these tokens between 1648 and 1672, when official production of farthings resumed and private production was suppressed.

Another period of coin shortage occurred in the late 18th Century, when the Royal Mint almost ceased production. Traders once again produced tokens, but they were now machine made and typically larger than their 17th Century predecessors with values of a halfpenny or more. While many were used in trade, they were also produced for advertising and political purposes, and some series were produced for the primary purpose of sale to collectors. These tokens are usually known as "Conder" tokens in the United States.

These were issued by a trader in payment for goods with the agreement that they will be redeemed in goods to an equivalent value at the traders own outlets. The transaction is therefore one of barter, with the tokens playing a role of convenience, allowing the seller to receive his goods at a rate and time convenient to himself and the trader to lock the holder of the token coin to his shop. Trade tokens often change slowly and subtly into barter tokens over time, as evidence by the continued circulation of former trade tokens when the need for their use had passed.

Because of weight, the U.S. Treasury Department does not ship coins to the Armed Forces serving overseas; so, Army and Air Force Exchange Service officials chose to make pogs in denominations of 5, 10 and 25 cents. The pogs are about 38mm (1.5816" to be exact) in diameter and feature various military-themed graphics.

The collecting of trade tokens, is called "exonumia," and includes other types of tokens, including transit tokens, encased cents, and many others. In a narrow sense, trade tokens are the "good for" tokens, issued by merchants. Generally they have a merchants name, sometimes a town and state, and also the required "good for 5¢" (or other denomination) legend somewhere on the token. Types of merchants that issued tokens include general stores, grocers, department stores, meat markets, drug stores, saloons, bars, taverns, barbers, coal mines, lumber mills, and many other businesses. The era of 1870 thru 1920 marked the highest use of "trade tokens" in the United States, spurred by the proliferation of saloons, billiard halls, bakerys, and general stores in rural areas. Thousands of small general stores and merchandise stores were found all over the United States, in almost every small town, and many of them used trade tokens to promote trade and extend credit to customers. Aluminum tokens almost always date after 1890.

Slot machine tokens

Metal token coins are used in lieu of cash in some slot machines in casinos.

Money is exchanged for the token coins or chips in a casino at the casino cage, at the gaming tables, or at a slot machine and at a cashier station for slot token coins. The tokens are interchangeable with money at the casino. They generally have no value outside out of the casino.

After the increase in the value of silver stopped the circulation of silver dollar coins around 1964, casinos rushed to find a substitute, as most slot machines at that time used that particular coin. The Nevada State Gaming Control Board consulted with the U.S. Treasury, and casinos were soon allowed to start using their own tokens to operate their slot machines. The Franklin Mint was the main minter of tokens at that time.

In 1971, many casinos adopted the Eisenhower dollar for use in machines and on tables. When the dollar was replaced with the Susan B. Anthony dollar in 1979, most casinos reinstituted tokens, fearing confusion with quarters and not wishing to extensively retool their slot machines. Those casinos which still use tokens in slot machines still use Eisenhower-sized ones.

In many jurisdictions, casinos are not permitted to use currency in slot machines, necessitating tokens for smaller denominations.

Tokens are being phased out of many casinos in favor of coin less machines which accept banknotes and print receipts for payout. (These receipts can also be inserted into the machines.)

Staff tokens

Staff tokens were issued to staff of businesses in lieu of coin. In the 1800s the argument supporting payment to staff was the shortage of coin in circulation, but in reality employees were forced to spend their wages in the company's stores at highly inflated prices - resulting in an effective dramatic lowering of their actual salary and disposable income.

Other sources of tokens

Railways and public transport agencies used fare tokens for years, to sell rides in advance at a discount, or to allow patrons to use turnstiles geared only to take tokens (as opposed to coins, currency, or fare cards).

- Car washes - Though their use has decreased in favor of coins and credit cards

- Video arcades

- Parking garages

- Subways

- Public telephone booths in countries with unstable currency were usually configured to accept token coins that were sold by the telephone company for variable prices. This system was in effect in Brazil until 1997 when magnetic cards were introduced. The practice was also recently discontinued in Israel,[4] leading to a trend of wearing the devalued tokens from necklaces.[5]

- Fast food restaurants - Often given to children to collect and redeem for prizes

- Niceties token - A token to encourage politeness.

- Commemorative coins have been produced with no monetary value to distribute by a company, country or organization.

In North America tokens were originally issued by traders from the 1700s in regions where national or local colonial governments did not issue enough small denomination coins for circulation. They were later used to create a monopoly; to pay labour; for discounts (pay in advance, get something free or discounted); or for a multitude of other reasons. In the United States, a well-known type is the wooden nickel, a five-cent piece distributed by cities to raise money for their anniversaries in the 1940s to 1960s.

Local stores, saloons and mercantiles, would issue their own tokens as well, spendable only in their own shops. Railways and public transport agencies have used fare tokens for years to sell rides in advance at a discount. Many transport organizations still offer their own tokens for bus and subway services, toll bridges, tunnels, and highways, although the use of computer-readable tickets has replaced these in some areas.

Churches used to give tokens to members passing a religious test prior to the day of communion, then required the token for entry. While mostly Scottish Protestant, some U.S. churches used communion tokens. Generally, these were pewter, often cast by the minister in church-owned molds. Replicas of these tokens have been made available for sale at some churches recently.

Notes

- ↑ N. Mahajan argues that Indian coins were the world's first coins in a book to be published by S. Hirano

- ↑ Government of Kerala Official website refers to Karshapanam as one of the oldest coins to be circulated in India

- ↑ M. Mitchiner, pp. 741-742

- ↑ http://www.mr-t.co.il/catalog3.html

- ↑ http://www.shekynecky.com/catalog.aspx?Merchant=shekynecky2&DeptID=227919

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Denis R. Cooper: The art and craft of coinmaking. A history of Mining Technology. London: Spink, 1988. ISBN 0-907605-27-3.

- A Case for the World's First Coin: The Lydian Lion

- "Church Tokens," New York Times, 11 April 1993

External links

- ANA

- Atlantic Provinces Numismatic Association providing news, events, latest releases from around the world, forums, and much more.

- CoinFacts.com - The Internet Encyclopedia of US Coins Free information on United States Coins, including pricing, rarity, and historical information.

- Ancient Greek Coins: Free Coin Organizer

- Coincat - An online coin catalog

- Coin Talk Forum - Community website for numismatists and coin collectors

- Numismopolis-Ancient Coin collecting, Ancient Minting, and Experimental archaeology. - includes information about collecting and ancient minting

- Challenge Coin Association

- Coin Image Database

- Silver Coins - How to identify counterfeit silver coins.

- CoinLink - Coin news, Directory of Numismatic sites

- World Coin Gallery - Self-proclaimed largest coin site in the world, with over 10,000 coins

- World's First Coin The Lydian Lion

- World Coin Gallery - Self-proclaimed largest coin site in the world, with over 10,000 coins

- World's First Coin The Lydian Lion

- 中国古銭譜("Chinese old coins directory," site in Japanese with texts and photos of many Chinese, Japanese, Korean&Vietnamese old coins)

- 中国造币—钱币鉴赏("Chinese made coins-seeing coins," site in Simplified Chinese about Chinese coins)

- Ancient Greek Coins: Free Coin Organizer

- Museum of Bank notes and Coins(in Japanese)

- The currency tokens of Strachan and Co

- Exonumia

- Token Collecting Organization

- The Conder Tokens Enthusiast - resources regarding 18th Century English Provincial token coinage

- A reference site on AAFES pogs: tokens currently in use by US armed forces overseas.

- An educational site on trade tokens in the USA, Token Tales.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.