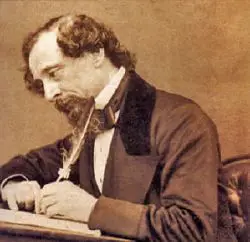

Charles Dickens

| Charles Dickens |

|---|

| Born |

| February 7, 1812 Portsmouth, Hampshire, England |

| Died |

| June 9, 1870 England |

Charles John Huffam Dickens (February 7, 1812 – June 9, 1870) was an English novelist of the Romantic and Victorian eras and one of the most popular writers in the English language. His works have continued to endure in public memory for their vivid characterization, poignant drama, and moral insight. Lifelong rival of the wealthy writer William Makepeace Thackeray, Dickens rose up from destitute poverty to become a truly "self-made man"—one of the first writers to support himself, and successfully so, entirely by his art. He was remarkable not only for his penetrating insight into human nature, but for the tremendous speed with which he was able to produce stories, novels, and other writings. The only writers of his age who can compare with him for sheer volume of published materials would be Honoré de Balzac and Henry James.

Dickens was not merely prolific, however. He was, as many writers, philosophers, and even political leaders have pointed out, one of the most politically revolutionary figures of his times. Having been born into a middle-class family that, early in his childhood, went bankrupt, Dickens experienced the underbelly of London society firsthand. Like the French novelists Victor Hugo and Emile Zola, Dickens brought to the foreground aspects of society that had rarely been depicted. But unlike the great French and Russian realists, Dickens' originality derived from his presentation of "types"—Uriah Heep, Mr. Macawber, Miss Havisham, Mrs. Jellyby, Ebenezer Scrooge, Fagin, among countless others—vividly drawn caricatures that endure in memory because Dickens' genius imbues each with an uncanny verisimilitude.

Dickens depicted to generations of readers the injustices and immoralities of a world corrupted by industrial power. He remains among the most beloved writers in the world for his enduring qualities of compassion, faith, generosity, and empathy for humanity.

Life

Dickens was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire to John Dickens (1786–1851), a naval pay clerk, and his wife Elizabeth Dickens neé Barrow (1789–1863). When he was five, the family moved to Chatham, Kent. At age ten, his family relocated to 16 Bayham Street, Camden Town in London. His early years were an idyllic time. He thought himself then as a "very small and not-over-particularly-taken-care-of boy." He spent his time outdoors, reading voraciously with a particular fondness for the picaresque novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. He talked later in life of his extremely poignant memories of childhood and his continuing photographic memory of people and events that helped bring his fiction to life. His family was moderately well-off, and he received some education at a private school but all that changed when his father, after spending too much money entertaining and retaining his social position, was imprisoned for debt. At the age of twelve, Dickens was deemed old enough to work and began working for ten hours a day in Warren's boot-blacking factory, located near the present Charing Cross railway station. He spent his time pasting labels on the jars of thick shoe polish and earned six shillings a week. With this money, he had to pay for his lodging and help to support his family, which was incarcerated in the nearby Marshalsea debtors' prison.

After a few years, his family's financial situation improved, partly due to money inherited from his father's family. His family was able to leave the Marshalsea, but his mother did not immediately remove him from the boot-blacking factory, which was owned by a relation of hers. Dickens never forgave his mother for this and resentment of his situation and the conditions under which working-class people lived became major themes of his works. Dickens told his biographer John Forster, "No advice, no counsel, no encouragement, no consolation, no support from anyone that I can call to mind, so help me God!" In May 1827, Dickens began work as a law clerk, a junior office position with potential to become a lawyer. He did not like the law as a profession and after a short time as a court stenographer he became a journalist, reporting parliamentary debate and traveling Britain by stagecoach to cover election campaigns. His journalism formed the basis of his first collection of pieces Sketches by Boz and he continued to contribute to and edit journals for much of his life. In his early twenties he made a name for himself with his first novel, The Pickwick Papers.

On April 2, 1836, he married Catherine Thompson Hogarth (1816–1879), with whom he was to have ten children, and set up home in Bloomsbury. In the same year, he accepted the job of editor of Bentley's Miscellany, a position he would hold until 1839, when he had a falling out with the owner. Dickens was also a major contributor for two other journals, Household Words and All the Year Round. In 1842, he traveled together with his wife to the United States; the trip is described in the short travelogue American Notes and forms the basis of some of the episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit. Dickens' writings were extremely popular in their day and were read extensively. In 1856, his popularity allowed him to buy Gad's Hill Place. This large house in Higham, Kent was very special to the author as he had walked past it as a child and had dreamed of living in it. The area was also the scene of some of the events of William Shakespeare’s Henry IV, part 1 and this literary connection pleased Dickens.

Dickens separated from his wife in 1858. In Victorian times, divorce was almost unthinkable, particularly for someone as famous as he was. He continued to maintain her in a house for the next twenty years until she died. Although they were initially happy together, Catherine did not seem to share quite the same boundless energy for life that Dickens had. Her job of looking after their ten children and the pressure of living with and keeping house for a world-famous novelist apparently wore on her. Catherine's sister Georgina moved in to help her, but there were rumors that Charles was romantically linked to his sister-in-law. An indication of his marital dissatisfaction was conveyed by his 1855 trip to meet his first love, Maria Beadnell. Maria was by this time married as well, and, in any event, she apparently fell short of Dickens' romantic memory of her.

On June 9, 1865, while returning from France to see Ellen Ternan, Dickens was involved in the Staplehurst rail crash in which the first six carriages of the train plunged off of a bridge that was being repaired. The only first-class carriage to remain on the track was the one in which Dickens was berthed. Dickens spent some time tending the wounded and the dying before rescuers arrived. Before finally leaving, he remembered the unfinished manuscript for Our Mutual Friend, and he returned to his carriage to retrieve it.

Dickens managed to avoid an appearance at the inquiry into the crash, as it would have become known that he was traveling that day with Ellen Ternan and her mother, which could have caused a scandal. Though unharmed, Dickens never really recovered from the Staplehurst crash, and his previously prolific writing was reduced to completing Our Mutual Friend and starting the unfinished The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Much of his time was taken up with public readings from his best-loved novels. Dickens was fascinated by the theater as an escape from the world. The traveling shows were extremely popular, and on December 2, 1867, Dickens gave his first public reading in the United States at a New York City theater. The effort and passion he put into these readings with individual character voices is thought to have contributed to his death.

Five years to the day after the Staplehurst crash, on June 9, 1870, Dickens died after suffering a stroke. Contrary to his wish to be buried in Rochester Cathedral, he was buried in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey. The inscription on his tomb reads: "He was a sympathiser to the poor, the suffering, and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England's greatest writers is lost to the world." Dickens' will stipulated that no memorial be erected to honor him.

Literary style

Characters

Dickens' characters are among the most memorable in English literature and certainly their names are among the most familiar. The likes of Ebenezer Scrooge, Fagin, Mrs. Gamp, Charles Darnay, Oliver Twist, Wilkins Micawber, Pecksniff, Miss Havisham, Wackford Squeers, and many others are well known. One “character” most vividly drawn throughout his novels is London itself. From the coaching inns on the outskirts of the city to the lower reaches of the Thames River, all aspects of the capital are described by someone who truly loved London and spent many hours walking its streets.

Episodic writing

Most of Dickens' major novels were first written in monthly or weekly installments in journals such as Master Humphrey's Clock and Household Words, later reprinted in book form. These installments made the stories cheap, accessible to the public and the series of regular cliff-hangers made each new episode widely anticipated. Legend has it that American fans even waited at the docks in New York, shouting out to the crew of an incoming ship, "Is Little Nell [of The Old Curiosity Shop] dead?" Part of Dickens' great talent was to incorporate this episodic writing style but still end up with a coherent novel at the end. Nevertheless, the practice of serialized publication that left little time for cautious craftsmanship exposed Dickens to criticism of sentimentality and melodramatic plotting.

Among his best-known works—Great Expectations, David Copperfield, The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, A Tale of Two Cities, and A Christmas Carol, among them—were all written and originally published in this serialized style. Dickens was usually keen to give his readers what they wanted, and the monthly or weekly publication of his works in episodes meant that the books could change as the story proceeded at the whim of the public. A good example of this is the American episodes in Martin Chuzzlewit, which were put in by Dickens in response to lower than normal sales of the earlier chapters. In Our Mutual Friend, the inclusion of the character of Riah was a positive portrayal of a Jewish character after he was criticized for the depiction of Fagin in Oliver Twist.

Social commentary

Dickens' novels were, among other things, works of social commentary. He was a fierce critic of the poverty and social stratification of Victorian society. Throughout his works, Dickens retained an empathy for the common man and a skepticism for the fine folk. Dickens' second novel, Oliver Twist (1839), was responsible for the clearing of the actual London slum that was the basis of the story's Jacob's Island. His sympathetic treatment of the character of the tragic prostitute Nancy humanized such women for the reading public—women who were regarded as "unfortunates," inherently immoral casualties of the Victorian class/economic system. Bleak House and Little Dorrit elaborated expansive critiques of the Victorian institutional apparatus: the interminable lawsuits of the Court of Chancery that destroyed people's lives in Bleak House and a dual attack in Little Dorrit on inefficient, corrupt patent offices and unregulated market speculation.

Major Works

The Bildungsromans: Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, and Great Expectations

Some of Dickens' most memorable novels fall into the category of the bildungsroman, a popular form of novel in the nineteenth century. Bildungsroman, a German term, roughly translates as "novel of education." Novels of this type relate the story of a protagonist who begins in a state of relative ignorance and then, as the novel progresses, gradually acquires knowledge, developing character through experiencing the events of the plot as they unfold.

Dickens used this form in part because it fit nicely with the social protest prevalent in his work. Due to his own painful childhood experiences, Dickens was especially sympathetic to the plight of children in a heartless world. In Oliver Twist (1837–1839) he uses a child protagonist exposed to the evils of industrial society as a social commentary. The eponymous protagonist is an orphan born as a virtual slave in a child workhouse. His fellow child workers coerce him into asking, one day, for an extra helping of food, and his employer is so offended that he sells young Oliver off to be an apprentice to a cruel undertaker. Oliver experiences only more abuse as a meager apprentice, and flees to London where he encounters the world of crime and becomes (unwittingly) the lackey of a boy criminal. As Oliver continues to spiral into London's underworld, however, he is rescued by two virtuous people: Nancy, the sister of a crime-leader Oliver works for, and Mr. Brownlow, a wealthy nobleman. In due course, all of the persons who have wronged Oliver get their just deserts, and, although Nancy is tragically murdered by her criminal brother, Oliver himself goes on to live happily ever after, once it has been revealed that he is a distant relative of Mr. Brownlow, and heir to a grand inheritance. The coincidences and the sentimental righting of wrongs in Oliver Twist are characteristic of Dickens' novels.

In David Copperfield (1849–1850), Dickens would return to the bildungsroman again, this time using a first-person narrator to great effect. In the novel, the eponymous David's father dies before he is born, and about seven years later, his mother marries Mr. Murdstone. David dislikes his stepfather and has similar feelings for Mr. Murdstone's sister Jane, who moves into the house soon afterwards. Mr Murdstone. thrashes David for falling behind with his studies. During the thrashing, David bites him and is sent away to a boarding school, Salem House, with a ruthless headmaster, Mr. Creakle. The apparently cruel school system of Victorian England was a common target for criticism in Dickens and elsewhere.

David returns home for the holidays to find out that his mother has had a baby boy. Soon after David goes back to Salem House, his mother dies and David has to return home immediately. Mr. Murdstone sends him to work in a factory in London of which he is a joint owner. The grim reality of hand-to-mouth factory existence echoes Dickens' own travails in a blacking factory. After escaping the factory, David walks all the way from London to Dover, to find his only known relative—his eccentric Aunt Betsy Trotwood. The story follows David as he grows to adulthood, extending, as it were, the story of hardscrabble coming-of-age found in Oliver Twist. In typical Dickens fashion, the major characters get some measure of what they deserve, and few narrative threads are left hanging. David first marries the beautiful but empty-headed Dora Spenlow, but she dies after suffering a miscarriage early in their marriage. David then does some soul-searching and eventually marries and finds true happiness with Agnes Wickfield, his landlord's daughter, who had secretly always loved him. The novel, hence, is a story not only of hardship in urban London but redemption through harmonious love, a sentimental theme Dickens would frequently return to throughout his works.

Finally, in Great Expectations, (1860–1861) Dickens returns once again to the theme of coming-of-age. In this novel, the protagonist, Pip, is a young man who, unlike David Copperfield or Oliver Twist, is born into relatively agreeable circumstances, living with his sister and her blacksmith-husband, Joe. Pip unexpectedly finds work as a companion to the wealthy, but eccentric Miss Havisham, and her adopted daughter, Estella, and through this connection he becomes enamored with the idea of becoming a gentleman. Pip's hopes are soon realized when he suddenly inherits the "great expectation" of a large bounty of property. At the behest of an anonymous benefactor, Pip begins a new life learning to be a gentleman. He moves to London, where tutors teach him all the various details of being an English gentleman, such as fashion, etiquette, and the social graces. Eventually, Pip adjusts to his new life, so much so that when Joe seeks Pip out, he is turned away because Pip has become ashamed of his humble beginnings. Finally, in the novel's third act, Pip meets his benefactor, and is gradually introduced to the other side of London to which, as a gentleman, he had never been exposed. Pip is shocked and ashamed at his own arrogance, and begins to reconsider his ways. Despite the fact that Dickens is a sentimental novelist, the work originally ended tragically, but Dickens was implored by his editors to give the novel a happy ending to satisfy his public. This alternate ending has remained to this day the definitive version, though it is unclear how satisfied Dickens was with the change. The novel can be seen rather easily as a sort of inverted version of Oliver Twist, in which a character who early in life acquires relative affluence is brought up into high society only to gradually realize the great injustices lurking just beneath the surface.

All of these novels serve to illustrate Dickens' attitudes towards the oppression of the poor, the cruel treatment of children, and the indifferent attitudes of the so-called "noble" classes to the injustices common to the industrial England of his times. With irony and wit, Dickens paints a portrait of London that shocked many of his readers, and ultimately impelled a great many to call for social change. But Dickens was first and foremost a writer, not a social crusader. His sentimental stories, with their happy endings for their protagonists and just deserts for their antagonists fed the demands of his audience for a sense of justice, mercy, and kindness in the imaginary world of his creation that did not exist within society.

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities (1859) is considered one of Dickens' most important works, both for the mastery of its writing and for the historical gravitas of its subject matter. It is a novel strongly concerned with themes of guilt, shame, and patriotism, all viewed through the lens of the revolutions, which were sweeping the Europe of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The novel covers a period in history between 1775 and 1793, from the American Revolutionary War until the middle period of the French Revolution. The plot centers on the years leading up to French Revolution and culminates in the Jacobin Reign of Terror. It tells the story of two men, Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, who look very alike, but are entirely different in character. Darnay is a romantic descended from French aristocrats, while Carton is a cynical English barrister. The two are in love with the same woman, Lucie Manette: one of them will give up his life for her, and the other will marry her. The novel itself is a grand overview of the revolutionary times, as well as of the great injustices committed by people on both sides. The two protagonists, who at the beginning are diametric opposites, one a French nobleman and the other a cynical Englishman, are ultimately both transformed by love, both becoming, in their different ways, heroes in a time of a chaos.

Plot Summary

The book starts off with the banker, Jarvis Lorry, who receives a message that a former friend, Dr. Manette, who has been imprisoned in Paris for over 18 years, has finally been released. Mr. Lorry arrives at Dover in the late morning. When Lucie Manette, Dr. Manette's daughter, arrives, Mr. Lorry introduces himself and proceeds to divulge the nature of her involvement in his current business in Paris. Mr. Lorry informs her that it is his duty to return the poor doctor to England, and he asks Lucie for her assistance in nursing him back to health.

Meanwhile, Charles Darnay, an émigré, is tried for spying on North American troops on behalf of the French. Lucie Manette and her father testify reluctantly against Darnay because he had sailed with them on their return trip from France to England. Darnay is, in the end, released because the people implicating him are unable to discern the difference between him and his lawyer, Mr. Stryver's assistant, Sydney Carton.

After seeing Lucie's sympathy for Charles Darnay during his trial, Sydney Carton becomes enamored with her and jealous of Darnay because of her compassion for him, wishing to take his place. Charles Darnay returns to France to meet his uncle, a Marquis. Darnay and the Marquis' political positions are diametrically opposed: Darnay is a democrat and the Marquis is an adherent of the ancient regime. Returning to England after the Marquis' death, Darnay asks Dr. Manette for his consent in wedding Lucie. At nearly the same time, Sydney Carton confesses his love to Lucie, but tells her that he will not act on it because he knows he is incapable of making her happy. He tells her that she has inspired him to lead a better life. With Carton out of the way, Darnay and Manette are happily married.

Later in time in the narrative, in mid-July 1789, Mr. Lorry visits Lucie and Charles at home and tells them of the inexplicable uneasiness in Paris. Dickens then promptly cuts to the Saint Antoine faubourg to enlighten the reader: the citizens of Paris are storming the Bastille. A letter arrives for Darnay revealing his long lost-identity as a French marquis. The letter beseeches Darney to return to France and assume his title. He makes plans to travel to a revolutionary Paris in which the Terror runs unabated, blithely indifferent to the consequences of his actions.

Darnay is denounced by the revolutionaries as an émigré, an aristocrat, and a traitor, however his military escort brings him safely to Paris where he is imprisoned. Dr. Manette and Lucie leave London for Paris and meet up with Mr. Lorry soon after arrival. When it is discovered that Darnay had been put in prison, Dr. Manette decides to try to use his influence as a former Bastille prisoner to have his son-in-law freed. He defends Darnay during his trial and he is acquitted of his charges. Shortly after, however, Darnay is taken to be put back on trial under new charges.

When Darnay is brought back before the revolutionary tribunal, he is sentenced to die within 24 hours. On the day of his execution, Darnay is visited by Carton, who, because of his love for Lucie, offers to trade places with him, as the two look very much alike. Darnay is not willing to comply, so Carton drugs him, and has him taken to the carriage waiting for himself. Darnay, Dr. Manette, Mr. Lorry, Lucie, and her child then make haste to leave France, with Darnay using Carton's papers to pass inspection. The novel concludes with the death of Sydney Carton, and his famous last words, "It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known."

A Christmas Carol

Although not one of his greater works in terms of its literary qualities, A Christmas Carol is indisputably Dickens' most popular creation. It takes the form of a Victorian morality play, where Ebenezer Scrooge, a wealthy miser who is cruel to everyone he meets, encounters the three ghosts of Christmas Past, Christmas Present, and Christmas Yet to Come on the night of Christmas Eve. The first of these three ghosts shows Scrooge visions from some of the happiest and saddest moments in his own past, including the cruelty shown to him by his own father, and his devotion to his business at the cost of the one woman he loved. The second ghost, of Christmas Present, reveals to Scrooge the miseries of those celebrating Christmas around him, including Tiny Tim, the ill child of one of Scrooge's employees who is on the verge of death because, on Scrooge's meager wages, his family cannot afford to pay for firewood and Christmas dinner. Finally, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come shows Scrooge a vision of his own miserable future and death; the few mourners who appear at Scrooge's funeral have nothing kind to say about him.

After these visions, Scrooge experiences a complete change of heart. Realizing that he must change his life, he immediately visits Tiny Tim, showering gifts on the family, and merrily joining in the Christmas spirit. The story concludes with Scrooge returning to the warm and kind-hearted person he once was, with happiness for all. Dickens' Carol has become one of the most enduring Christmas stories of all time, and reproductions of the story continue to be produced year after year at Christmas pageants around the world.

Legacy

Charles Dickens first full novel, The Pickwick Papers (1837), brought him immediate fame and this continued right through his career. His popularity has waned little since his death. He is still one of the best known and most read of English authors. At least 180 movies and TV adaptations have been produced based on Dickens' works. Many of his works were adapted for the stage during his own lifetime and as early as 1913 a silent film of The Pickwick Papers was made. His characters were often so memorable that they took on a life of their own outside his books. Gamp became a slang expression for an umbrella based on the character Mrs. Gamp. Pickwickian, Pecksniffian, and Gradgrind all entered dictionaries due to Dickens' original portraits of such characters who were quixotic, hypocritical, or emotionlessly logical. Sam Weller, the carefree and irreverent valet of The Pickwick Papers, was an early superstar, perhaps better known than his author at first. A Christmas Carol is his best-known story, with new adaptations almost every year. It is also the most-filmed of Dickens's stories, many versions dating from the early years of cinema. This simple morality tale with both pathos and its theme of redemption, for many, sums up the true meaning of Christmas and eclipses all other Yuletide stories in not only popularity, but in adding archetypal figures (Scrooge, Tiny Tim, the Christmas ghosts) to the Western cultural consciousness.

At a time when Britain was the major economic and political power of the world, Dickens highlighted the life of the forgotten poor and disadvantaged at the heart of empire. Through his journalism he campaigned on specific issues—such as sanitation and the workhouse—but his fiction was probably all the more powerful in changing public opinion about class inequalities. He often depicted the exploitation and repression of the poor and condemned the public officials and institutions that allowed such abuses to exist. His most strident indictment of this condition is in Hard Times (1854), Dickens' only novel-length treatment of the industrial working class. In that work, he uses both vitriol and satire to illustrate how this marginalized social stratum was termed "Hands" by the factory owners, that is, not really "people" but rather only appendages of the machines that they operated. His writings inspired others, in particular, journalists and political figures, to address class oppression. For example, the prison scenes in Little Dorrit and The Pickwick Papers were prime movers in having the Marshalsea and Fleet prisons shut down. As Karl Marx said, Dickens "issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together" (qtd. in Ackroyd 1990: 757). The exceptional popularity of his novels, even those with socially oppositional themes (Bleak House, 1853; Little Dorrit, 1857; Our Mutual Friend, 1865) underscored not only his almost preternatural ability to create compelling storylines and unforgettable characters, but also insured that the Victorian public confronted issues of social justice that had previously been ignored.

Dickens loved the style of eighteenth-century gothic romance, though by his time it had already become an anachronism. Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey was a well known pastiche. Dickens admired the vivid emotions of gothic fiction, despite the grotesque presence of the supernatural in the storylines.

His fiction, with often vivid descriptions of life in nineteenth-century England, has come to be seen, somewhat inaccurately and anachronistically, as symbolizing Victorian society (1837–1901), as expressed in the coined adjective, "Dickensian." In fact, his novels' time-span is from the 1780s to the 1860s. In the decade following his death in 1870, a more intense degree of socially and philosophically pessimistic perspectives invested British fiction; such themes were in contrast to the religious faith that ultimately held together even the bleakest of Dickens's novels. Later Victorian novelists such as Thomas Hardy and George Gissing were influenced by Dickens, but their works display a lack or absence of religious belief and portray characters caught up by social forces (primarily via lower-class conditions) that steer them to tragic ends beyond their control. Samuel Butler (1835–1902), most notably in The Way of All Flesh (1885; pub. 1903), also questioned religious faith but in a more upper-class milieu.

Novelists continue to be influenced by his books; for example, such disparate current writers as Anne Rice and Thomas Wolfe evidence direct Dickensian connections. Humorist James Finn Garner even wrote a tongue-in-cheek "politically correct" version of A Christmas Carol. Ultimately, Dickens stands today as a brilliant and innovative novelist whose stories and characters have become not only literary archetypes but also part of the public imagination.

Bibliography

Major novels

- The Pickwick Papers (1836)

- Oliver Twist (1837–1839)

- Nicholas Nickleby (1838–1839)

- The Old Curiosity Shop (1840–1841)

- Barnaby Rudge (1841)

- The Christmas books:

- A Christmas Carol (1843)

- The Chimes (1844)

- The Cricket on the Hearth (1845)

- The Battle of Life (1846)

- Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–1844)

- Dombey and Son (1846–1848)

- David Copperfield (1849–1850)

- Bleak House (1852–1853)

- Hard Times (1854)

- Little Dorrit (1855–1857)

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Great Expectations (1860–1861)

- Our Mutual Friend (1864–1865)

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood (unfinished) (1870)

Selected other books

- Sketches by Boz (1836)

- American Notes (1842)

- Pictures from Italy (1846)

- The Life of Our Lord (1846, published in 1934)

- A Child's History of England (1851–1853)

Short stories

- "A Child's Dream of a Star" (1850)

- "Captain Murderer"

- "The Child's Story"

- The Christmas stories:

- "The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain" (1848)

- "A Christmas Tree"

- "The Poor Relation's Story"

- "The Child's Story"

- "The Schoolboy's Story"

- "Nobody's Story"

- "The Seven Poor Travellers"

- "What Christmas Is As We Grow Older"

- "Doctor Marigold"

- "George Silverman's Explanation"

- "Going into Society"

- "The Haunted House"

- "Holiday Romance"

- "The Holly-Tree"

- "Hunted Down"

- "The Lamplighter"

- "A Message from the Sea"

- "Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy"

- "Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings"

- "Mugby Junction"

- "Perils of Certain English Prisoners"

- "The Signal-Man"

- "Somebody's Luggage"

- "Sunday Under Three Heads"

- "Tom Tiddler's Ground"

- "The Trial for Murder"

- "Wreck of the Golden Mary"

Essays

- In Memoriam W. M. Thackeray

Articles

- A Coal Miner's Evidence

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackroyd, Peter. 1991. Dickens. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060166021

- Chesterton, G.K. 2010. Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens. ValdeBooks. ISBN 978-1444456714

- Slater, Michael. 2009. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300112078

- Tomalin, Claire. 2012. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0143122050

External links

All links retrieved February 2, 2017.

- Works by Charles Dickens. Project Gutenberg

- The Complete Literary Works of Charles Dickens The Classic Literature Library

- A Charles Dickens Journal Timeline of Dickens' Life

- The Dickens Fellowship

- Charles Dickens Info

- The Dickens Page

- Dickens Museum Situated in a former Dickens House, 48 Doughty Street, London, WC1

- Dickens Birthplace Museum Old Commercial Road, Portsmouth

- Broadstairs Dickens Festival

- International Dickens Festival

- Dickens Christmas Fair in San Francisco

- Free audiobook of A Christmas Carol at LibriVox

- Appreciations and Criticisms of the Works of Charles Dickens by G. K. Chesterton

- Life of Charles Dickens, by Frank Marzials, at Project Gutenberg. 1887 publication with lengthy bibliography.

- Philadelphia's Statue of Dickens and Little Nell

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Charles_Dickens history

- Oliver_Twist history

- David_Copperfield history

- Great_Expectations history

- A_Tale_of_Two_Cities history

- A_Christmas_Carol history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.