Banks Island

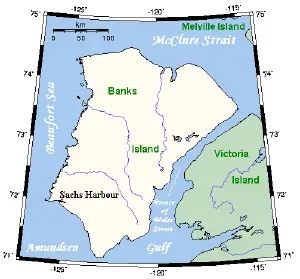

These Moderate resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer Images from June 14 and 16, 2002, show Banks Island (upper left) and Victoria Island (to the southeast) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Beaufort Sea |

| Coordinates | Coordinates: |

| Archipelago | Canadian Arctic Archipelago |

| Area | 70,028 km² (27,038 sq mi) (24th) |

| Length | 380 km (240 mi) |

| Width | 290 km (180 mi) |

| Highest point | Durham Heights (730 m (2,400 ft)) |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Largest city | Sachs Harbour |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 136 (as of 2010) |

| Density | 0.0016 people/km2 |

Banks Island is the westernmost island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. It is located in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada and is the fourth largest island in the archipelago. The Island is separated from its eastern neighbor, Victoria Island, by the Prince of Wales Strait and from the continental mainland by Amundsen Gulf to its south. The Beaufort Sea lies to the island's west. To the northeast, McClure Strait separates the island from Prince Patrick Island and Melville Island. The only permanent settlement on the island is Sachs Harbour, an Inuvialuit hamlet on the southwest coast.

Wildlife found there includes Arctic foxes, wolves, caribou, polar bears, and the world's largest concentration of Musk oxen. Since the mid-1990s Banks Island has become a Canadian Arctic focal point for studies of climate change.

Geography

The Canadian Arctic Archipelago is an archipelago north of the Canadian mainland in the Arctic. Situated in the northern extremity of North America and covering about 1,424,500 km² (550,003 sq mi), this group of 36,563 islands comprises much of the territory of Northern Canada—most of Nunavut and part of Northwest Territories.

The archipelago extends some 2,400 km (1,491 mi) longitudinally and 1,900 km (1,180.6 mi) from the mainland to Cape Columbia, the northernmost point on Ellesmere Island. The various islands of the archipelago are separated from each other and the continental mainland by a series of waterways collectively known as the Northwestern Passages. There are 94 major islands (greater than 130 km² (50 sq mi)) and 36,469 minor islands. Banks Island is the fourth largest in the archipelago, fifth largest in Canada, and 24th largest island in the world. It is administratively part of the Northwest Territories.

It covers an area of 70,028 square kilometers (27,038 sq mi). It is approximately 380 kilometers (240 mi) long, and at its widest point at the northern end, 290 kilometers (180 mi) across. The highest point of the island is in the south, Durham Heights, rising to about 730 metres (2,400 ft).[1]

The island is in the Arctic tundra climatic zone, characterized by long, extremely cold winters. The north part of the island is snow and ice covered, while the west coast is flat, sandy, and often shrouded in fog. Most of the remaining shoreline is flanked by sloping hills of gravel, vertical cliffs of sandstone and two-billion-year-old Precambrian rock. Parts of the island's sheltered interior valleys are remarkably lush and temperate during the short summer months, nearly resembling the sheep country of northern Scotland.[2]

Climate changes have occurred in recent years, such that sea-ice has been breaking up earlier than normal, taking seals farther south in the summer. Warming has brought various changes; salmon appeared for the first time in nearby waters between 1999 and 2001. New species of birds are migrating to the island, including robins and barn swallows, and more flies and mosquitos have been appearing.

The lives of the island's residents has always revolved around the natural environment; fishing, hunting, and travel. Thus they have considerable knowledge of weather conditions, permafrost, and even erosion patterns. In recent years they have begun to fear that their knowledge of weather patterns may fail, as recent climate changes have made the weather harder to predict.

Flora and fauna

Banks Island is home to the endangered Peary Caribou, the Barren-ground Caribou, seals, polar bears, arctic foxes, snowy owls and snow geese. Bird life includes such species as robins and swallows. The island has the highest concentration of muskoxen on earth, with estimates of 68,000 to 80,000 animals, approximately 20 percent of which reside in the Aulavik National Park in its northwest.[3]

The Aulavik National Park is a fly-in park that protects approximately 12,274 km (7,626.71 mi) of Arctic lowlands at the northern end of the island. The Thomsen River runs through the park, and is the northernmost navigable river (by canoe) in North America. Ptarmigan and ravens are considered the only year-round birds in the park, although 43 different species make seasonal use of the area.

Aulavik is considered a polar desert and often experiences high winds. Precipitation for the park is approximately 300 mm (12 in) per year.[3] In the southern regions of the park a sparsely vegetated upland plateau reaches a height of 450 m (1,500 ft) above sea level.[3] The park has two major bays, Castel Bay and Mercy Bay, and lies south of the McClure Strait.

The park is completely treeless, and Arctic Foxes, brown and Northern Collared Lemmings, Arctic Hares and wolves roam the rugged terrain. Birds of prey in the park include Snowy Owls, rough-legged hawks, Gyrfalcons, and Peregrine Falcons, who feed on the lemmings.

Musk oxen

Musk oxen had once lived on Banks Island but were believed to be nearly extinct there since the beginning of the twentieth century. Canadian biologists surveying the island's wildlife in 1952 saw one musk ox on their expedition. In the years that followed, musk-ox numbers steadily increased on the island and in 1961, a biologist counted 100 of them. By 1994, the numbers had exploded to 84,000—half of all of the musk-oxen in the world at the time. A 1998 estimate brought the number down to 58,000, a significant decrease but still a robust number.

The reason for the fall and rise of musk-oxen on Banks Island remains a mystery. Scientists disagree both about why the animals disappeared on Banks and why the species has experienced a phenomenal recovery there since the mid-twentieth century. Banks Island has the highest concentration of the animal on earth.[2]

History

While parts of the Arctic have been inhabited for nearly 4,000 years, the earliest archaeological sites found on Banks Island are Pre-Dorset cultural sites that date to approximately 1500 B.C.E. Site excavations have uncovered flint scrapers, bone harpoon heads and needles, along with the bones of hundreds of muskoxen.

The island seems to have had little activity from the period 800 B.C.E. to 1000 C.E. The few sites that exist from that era are on the southern part of the island, and exhibit characteristics of both the Eastern Arctic Dorset culture and their Western Arctic counterparts.

For the next 500 years, Thule peoples occupied several sites along the south coast of the island. Evidence exists of an economy based on harvesting sea mammals, particularly bowhead whales and ringed seals. Muskoxen were harvested from the northern reaches of the island, though in an expeditionary manner, as no evidence of settlements there exist.

Due to the cooling climate brought on by the Little Ice Age, much of Banks Island was deserted until the seventeenth century. The Thule migrated to smaller regions inland and developed necessary specialized hunting skills. As the climate warmed, they wandered further and re-established themselves as several closely related but locally distinct groups of Inuit. One of these groups, the Mackenzie Inuit, or Inuvialuit, occupied sites along the southern coast in the seventeenth through mid-nineteenth centuries.

European exploration of the island began in the early nineteenth century. In 1820 a member of the expedition of Admiral William Edward Parry saw land to the southwest of Melville Island. It was christened Banksland to honor Joseph Banks, an English naturalist, botanist, patron of the natural sciences, and president of the Royal Society of London.

It was not until 1850 that Europeans visited Banks Island. Robert McClure, commander of the HMS Investigator came to the area in search of the lost Franklin Expedition. The Investigator became trapped in the ice at Mercy Bay at the island's northern end. After three winters, McClure and his crew—who were by that time dying of starvation—were found by searchers who had traveled by sledge over the ice from a ship of Sir Edward Belcher's expedition. They hiked across the sea-ice of the strait to Belcher's ships, which had entered the sound from the east. McClure and his crew returned to England in 1854 on one of Belcher's ships. At the time they referred to the island as "Baring Island."

From 1855 to 1890 the Mercy Bay area was visited by the Copper Inuit of Victoria Island who came to salvage materials left by McClure's party. They also hunted the caribou and muskox in the area as evidenced by the large number of food caches.

In the twentieth century the area was popular with Inuvialuit due to the large numbers of foxes. Until the fur trade went into decline, fox trapping provided a source of income for people from as far away as the Mackenzie Delta and the North Slope of Alaska. This influx of people led to the establishment of Sachs Harbour, the only community on the island.[4]

Population

The only permanent settlement on Banks Island is the hamlet of Sachs Harbour, situated on its southwestern coast. According to Canada's 2006 census, the population was 122 individuals.[5] The town was named after the ship Mary Sachs, which was part of the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913.

The community's economy is based largely on hunting and trapping, but tourism also plays a small role. Most of the town lies within 250 yards of the shoreline. Residents also engage in ice fishing, harvesting fish from the Amundsen Gulf and the Beaufort Sea. Oil and gas exploration has provided jobs over the years for some Sachs Harbour residents—estimates of commercially recoverable oil in the Beaufort Sea range from four to 12 billion barrels, and there is believed to be between 13 and 63 trillion cubic feet (1,800 km3) of natural gas.

The two principal languages in the town are Inuvialuktun and English. The traditional name for the area is "Ikahuak," meaning "where you go across to." Bulk supplies of food and other items are brought by barge in the summer months and flights from Inuvik, some 325 miles (523km) to the southwest, operate all year.

The town hosts a goose hunt every spring—Banks Island being the home to the largest goose colony in North America. The community is also home to the largest commercial muskox harvests in Canada. Three quarters of the world's population of muskoxen roam the island. The first Grizzly-polar bear hybrid found in the wild near Sachs Harbour in April 2006.

Looking ahead

Banks Island has become a focal point for climate change studies in the Canadian Arctic. However, long-term climate and environmental data from the island is sparse. While much of the current knowledge is based on scientific findings; traditional knowledge, guided by generations of experience, can supplement modern findings. The Inuvialuit have generations of extensive knowledge of the Arctic environment, and most have voiced that current environmental changes are without precedent.

Changes in the environment as noted by the Sachs Harbour community include freeze-ups that are three to four weeks late. Intense, unpredictable weather and fluctuations in seasons have also been observed. Severe storms with wind, thunder, lightning, and hail and the disappearance of summer ice floes have also been noted. Earlier births of muskox, geese laying eggs earlier, and polar bears emerging from their dens earlier because of warming and thaw round out the list. Inuvialuit natives to Banks Island have also described catching species of Pacific salmon when traditionally such occurrences were unheard of. Too much open water in the winter makes harvesting animals difficult, as does the lack of snow in spring, the lack of sea ice in summer, increased freezing rain, and thinner ice.[6]

Historically, the Arctic peoples' lives have been intimately intertwined with the environment and they have survived and developed by adapting to environmental changes. However, the rate at which the changes the people of Banks Island are experiencing is rapid enough to be outside their realm of experience. It will be necessary to link traditional knowledge with scientific expertise in order to understand the potential impacts of climate change on the indigenous peoples.

Notes

- ↑ Historica Foundation of Canada. Banks Island Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ed Struzik. January-February, 2000. And Then There Were 84,000: The return of musk-oxen to Canada's Banks Island in recent decades is just one chapter of a beguiling Arctic mystery CBS Interactive. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Parks Canada.

- ↑ Parks Canada. History and culture Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Statistics Canada. All Data, Sachs Harbour Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ Dyanna Riedlinger, Climate Change and the Inuvialuit of Banks Island, NWT: Using Traditional Environmental Knowledge to Complement Western Science Arctic Institute of North America. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Canada. Banks Island, a Natural Area of Canadian Significance. Natural area of Canadian significance. Ottawa: Parks Canada, 1978. OCLC 31113171

- Cotter, R. C., and J. E. Hines. "Breeding Biology of Brant on Banks Island, Northwest Territories, Canada." Arctic. 54 (2001): 357-366. OCLC 107610126

- Gajewski, K., R. Mott, J. Ritchie, and K. Hadden. "Holocene Vegetation History of Banks Island, Northwest Territories, Canada." Canadian Journal of Botany. 78 (2000): 430-436. OCLC 197133460

- Holyoak, D. T. Notes on the Birds of Southwestern Banks Island, Northwest Territories, Canada. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club, 103(2) (June, 1983). OCLC 70523333

- Manning, T. H., E. O. Höhn, and A. H. Macpherson. The Birds of Banks Island, 1956. OCLC 4711934

- Stephens, L. E., L. W. Sobczak, and E. S. Wainwright. Gravity Measurements on Banks Island, N.W.T. Gravity map series, no. 150. Ottawa: Dept. of Energy, Mines and Resources, Earth Physics Branch, 1972. OCLC 85756011

- Struzik, Ed. "AND THEN THERE WERE 84,000 - The Return of Musk-Oxen to Canada's Banks Island in Recent Decades Is Just One Chapter of a Beguiling Arctic Mystery." International Wildlife. 30(1) (2000): 28.

- Will, Richard T. Utilization of Banks Island Muskoxen by Nineteenth Century Copper Inuit. [S.l.]: Boreal Institute for Northern Studies, 1983. OCLC 36799378

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Banks_Island history

- Canadian_Arctic_Archipelago history

- Aulavik_National_Park history

- Sachs_Harbour,_Northwest_Territories history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.