Alexander Griboyedov

Alexander Sergeyevich Griboyedov (Russian: Александр Сергеевич Грибоедов) (January 15, 1795 – February 11, 1829) was a Russian diplomat, playwright, and composer. As a writer, he is recognized as a homo unius libri, a writer of one book, whose fame rests on the brilliant verse comedy Woe from Wit, still one of the most frequently staged plays in Russia. This play was an important precursor to many of the finest modern satires, including the stories of Nikolai Gogol and his Dead Souls, which lampoon the bureaucracy of Imperial Russia as well as Mikhail Bulgakov's satiric short stories of the Soviet state and his masterpiece, Master and Margarita. The satiric form has long been employed in Russia due to the excessively authoritarian and often ineffectual nature of the Russian state.

Biography

Born in Moscow, Griboyedov studied at the Moscow State University from 1810 to 1812. During the Napoleonic War of 1812 he served in the cavalry, obtaining a commission in a hussar regiment, but saw no action and resigned in 1816. The following year, Griboyedov entered the civil service, and in 1818 was appointed secretary of the Russian legation in Persia.

He was later transferred to Republic of Georgia. He had commenced writing early and, in 1816, had produced on the stage at Saint Petersburg a comedy in verse called The Young Spouses (Молодые супруги), which was followed by other works of the same kind. But neither these nor the essays and verses which he wrote would have been long remembered but for the immense success gained by his comedy in verse Woe from Wit (Горе от ума, or Gore ot uma), a satire upon Russian society, which was dominated by the aristocracy during the nineteenth century.

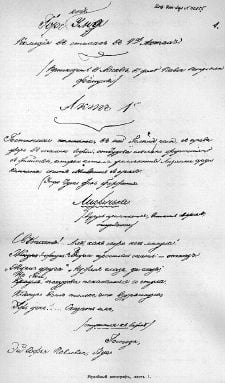

Griboyedov spent the summer of 1823 in Russia, completed his play and took it to Saint Petersburg. There, it was rejected by the censors. Many copies were made and privately circulated, but Griboyedov never saw it published. The first edition was printed in 1833, four years after his death. Only once did he see it on the stage, when it was acted by the officers of the garrison at Yerevan. He was arrested along with others for the conspiracy surrounding the Decembrist Revolt of 1825, as liberals pressed for reforms after the death of Tsar Alexander I of Russia. The leaders were rounded up and some were executed. Griboyedov, however, was able to exonerate himself.

Soured by disappointment, he returned to Georgia and made himself useful through his linguistic abilities to his relative, Count Ivan Paskevich during a Russo-Persian War (1826-1828), and was sent to Saint Petersburg with the Treaty of Turkamanchai in 1828. Brilliantly received there, he thought of devoting himself to literature, and commenced a romantic drama, A Georgian Night (Грузинская ночь, or Gruzinskaya noch).

Several months after his wedding to the 16-year-old daughter of his friend, Prince Alexander Chavchavadze, Griboyedov was suddenly sent to Persia as Minister Plenipotentiary. Soon after his arrival at Tehran, a crowd of Islamic religious fanatics stormed the Russian embassy. Griboyedov (along with almost everyone else inside) was slaughtered, and his body was so ill-treated by the mob for three days that it was at last recognized only by an old scar on his hand, due to a wound received in a duel. His body was taken to Tiflis and buried in the monastery of Saint David. His 16-year-old widow, Nina, on hearing of his death, gave premature birth to a child, who died a few hours later. She lived another 30 years after her husband's death, rejecting all suitors and winning universal admiration by her fidelity to his memory.

Woe from Wit

Woe from Wit (Russian: Горе от ума; also translated as "The Woes of Wit," "Wit Works Woe," etc.) is Griboyedov's comedy in verse, satirizing the society of post-Napoleonic Moscow, or, as a high official in the play styled it, "a pasquinade on Moscow." Its plot is slight; its merits are to be found in its accurate representation of certain social and official types—such as Famusov, the lover of old abuses, the hater of reforms; his secretary, Molchalin, servile fawner upon all in office; the aristocratic young liberal and Anglomaniac, Repetilov; who is contrasted with the hero of the piece, Chatsky, the ironic satirist just returned from Western Europe, who exposes and ridicules the weaknesses of the rest. His words echoing that outcry of the young generation of 1820 which reached its climax in the military insurrection of 1825, and was then sternly silenced by Nicholas I. Although rooted in the classical French comedy of Jean-Baptiste Molière, the characters are as much individuals as types, and the interplay between society and individual is a sparkling dialectical give-and-take.

The play, written in 1823 in the countryside (Tiflis), was not passed by the censorship for the stage and only portions of it were allowed to appear in an almanac for 1825. But it was read by the author to "all Moscow" and to "all Petersburg" and circulated in innumerable copies, so its publication effectively dates from 1825.

The play was a compulsory work in Russian literature lessons in Soviet schools, and is still considered a classic in modern Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union.

One of the main settings for the satire of Mikhail Bulgakov's novel The Master and Margarita is named after Griboyedov, as is the Griboyedov Canal in central Saint Petersburg.

Language

The play belongs to the classical school of comedy. The principal antecedent is Jean-Baptiste Molière. Like Denis Fonvizin before him, as well as the much of the Russian realistic tradition that followed (Tolstoy was an exception), Griboyedov lays far greater stress on the characters and their dialogue than on his plot. The comedy is loosely constructed, but Griboyedov is supreme and unique in creating dialogue and revealing character.

The dialogue is in rhymed verse, in iambic lines of variable length, a meter that was introduced into Russia by the fabulists as the equivalent of Jean de La Fontaine's vers libre, reaching a high degree of perfection in the hands of Ivan Krylov. Griboyedov's dialogue is a continuous tour de force. It always attempts and achieves the impossible—the squeezing of everyday conversation into a rebellious metrical form.

Griboyedov seemed to multiply his difficulties on purpose. He was, for instance, alone in his age to use unexpected, sonorous, punning rhymes. There is just enough toughness and angularity in his verse to constantly remind the reader of the pains undergone and the difficulties triumphantly overcome by the poet. Despite the fetters of the metrical form, Griboyedov's dialogue has the natural rhythm of conversation and is more easily colloquial than any prose. It is full of wit, variety, and character, and is a veritable store book of the best spoken Russian of a period. Almost every other line of the comedy has become part of the language, and proverbs from Griboyedov are as numerous as those from Krylov. For epigram, repartee, terse and concise wit, Griboyedov has no rivals in Russian.

Characters

Woe from Wit is above all a satire on human foibles in the manner of Molière. Thus, each character is a representative of types to be found in Griboyedov's Russia. His characters, while typical of the period, are stamped in the common clay of humanity. They all, down to the most episodic characters, have the same perfection of finish and clearness of outline.

Key characters include:

- Pavel Afanasyevich Famusov—the father, the head of an important department, the classic conservative of all time, the cynical and placid philosopher of good digestion, the pillar of stable society.

- Sofia Pavlovna—his daughter, the heroine neither idealized nor caricatured, with a strange, dryly romantic flavor. With her fixity of purpose, her ready wit, and her deep, but reticent, passionateness, she is the principal active force in the play and the plot is advanced mainly by her actions.

- Alexey Stepanovich Molchalin—Famusov's secretary living in his house, the sneak who plays whist (a card game) with old ladies, pets their dogs, and acts the lover to his patron's daughter.

- Alexandr Andreyevich Chatsky—the protagonist. Sometimes irrelevantly eloquent, he leads a generous, if vague, revolt against the vegetably selfish world of Famusovs and Molchalins. His exhilarating, youthful idealism, his ego, his élan is of the family of Romeo. It is significant that, in spite of all his apparent lack of clear-cut personality, his part is the traditional touchstone for a Russian actor. Great Chatskys are as rare and as highly valued in Russia as are great Hamlets in Britain.

- Repetilov—the Anglomaniac orator of the coffee room and of the club, burning for freedom and stinking of liquor, the witless admirer of wit, and the bosom friend of all his acquaintances.

As representative types, a number of the characters have names that go a long way toward describing their personality in Russian. Molchalin's name comes from the root of the verb molchat, to be silent, and he is a character of few words. Famusov's name actually comes from the Latin root fama, meaning talk or gossip, of which he does a great deal. The root of Repetilov is obviously from repetitive or repetitious, a commentary on his banalities. Colonel Skalozub derives from skalit' zuby, to bear one's teeth or to grin.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mirsky, D. P. A History of Russian Literature from its Beginnings to 1900. Edited by D. S. Mirsky and Francis J. Whitfield. New York: Vintage Books, 1958. ISBN 0810116790

- Terras, Victor. A History of Russian Literature. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991. ISBN 0756761484

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Горе от ума – full text in Russian

- Горе от ума – full text in Russian at Alexei Komarov's Internet Library

- Woe from Wit – full text of English translation by A Vagapov, 1993

- The Woes of Wit – Alan Shaw's translator's introduction

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.